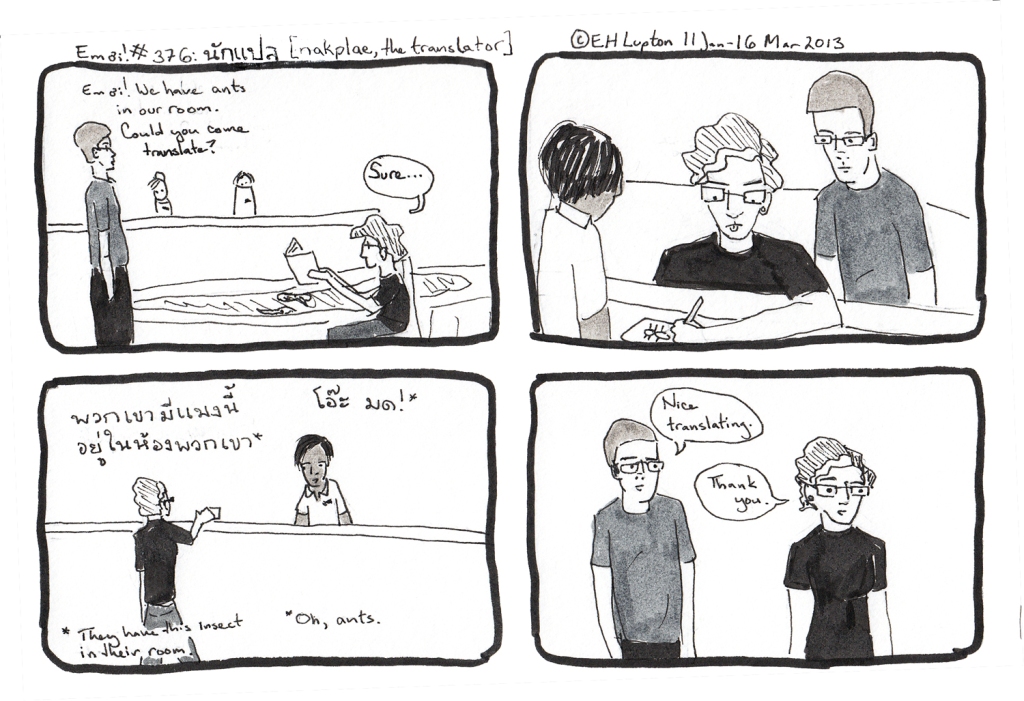

Another sketch from our trip to Thailand. This actually happened at a down-at-its-heels hotel in Chiang Mai. Eventually Andy and Sara got to move to a slightly better room…but they didn’t manage to get one with a double bed. At the time, I complained that we had landed in the Chiang Mai version of Pham Ngu Lao, a street in Ho Chi Minh City known for cheap/seedy backpacker hotels. I think, having looked at a lot of other hotel reviews, that most places in Chiang Mai are like that. It wasn’t a bad hotel, exactly…well, it was. But it was clearly a nice hotel about ten or fifteen years ago when it was built. And then nothing was updated again.

There was a fiendish device on the bedside table. You can see it in this photo to the right (and now you all know the name of the hotel, oops.). You push a button and the lights turn on or off. Somehow we managed to push the buttons so that around about five o’clock in the morning, the lights started to turn on and off by themselves. You can imagine, given how jet lagged I was, how well that went over. I thought the place was haunted. I guess this was state-of-the-art in like…1980.

I’m maybe a bit bitter because the room smelled like smoke. But later on that day, after our freaky awakening, B got sick and basically slept in the room for 12 hours. I figured at least the sheets were clean and the AC worked.

These are my preliminary sketches of Andy, done to prep for this comic and Em oi! #374. I guess he’s lost a fair amount of weight since he got back to Texas, so these are not entirely accurate.

Today we went to see Oz the Great and Powerful, Sam Raimi’s prequel to The Wizard of Oz. I found that in the years since I first saw the original, the details of the land of Oz have gotten tangled up in my head with other fantasy places, like Wonderland, Middle Earth, and Australia. There were some details that struck me as kind of bizarre–why would you have a field of poppies that can cause everlasting sleep right next to the Emerald City? Isn’t that a liability case waiting to happen? The witches were also interesting, although I was sad that they went with the old trope of “dark hair bad, blond-y good-y.” Glinda the good witch, played by Michelle Williams, reminded me of Galadriel (blond hair, long white gown, kind of ethereal expression). Then I remembered that amazing scene where Galadriel almost takes the ring, but doesn’t. Wow, she’s a really interesting character in that scene. Too bad Glinda was just blandly kind. Of course it is nice to have one character who is kind, but… Also I am not sure how I feel about the turning-green-as-externalization-of-internalized-self-loathing? And of course no one can out-evil Margaret Hamilton.

There was a lot about families in it though, and a kind of magical scene where Oz (played by James Franco) glues a little china doll’s legs back on. I maybe got a little verklempt.

Now that I think about it, maybe Glinda was a bit more manipulative in the first film, since she doesn’t tell Dorothy how to use the slippers to get home until the very end of the book…

Today I got up and ran 18 miles (well, 18.25). It was an interesting run. I was up in the night with indigestion (from 2:30-4 am) and only got out of bed around 8:30, an hour later than my alarm was set for. Actually, at 8:15, Bryan rolled over and said, “Why are you still here?” I took some drugs and set out, going easy, waiting to see if anything bad would happen…but nothing did. I got tired, since I did the whole run on only 190 calories (two gels, one 90 cal, one 100 cal) plus the glycogen stored from yesterday’s overeating (the thing that caused me so much trouble). Anyway, I mostly shuffled along at 10:30-10:40 minutes/mile, more than a minute slower than my planned race pace. Toward the end, I tried to pick things up and ran a 9:54, but then my stomach started to ache and said, “Don’t ever do that again,” so I finished slow. (I wasn’t going to call B to pick me up with two miles to go.) At least I finished.

This is wandering, probably because of my weird interrupted sleep. I’d better bring things to a stopping point.

This comic will be filed under P306.94 .L86 2013, for Philology. Linguistics—Language. Linguistic theory. Comparative grammar—Translating and interpreting—Translating services. In case you were curious, if you search for the heading “translation,” all you get is class numbers related to specific translations–translating the bible, translating Emile Zola into English, etc. The correct subject heading for translation as the subject of a work is “translating and interpreting.” I had to look it up.