Today I woke up and I knew it was the day: I was going to return my library books. This is important if you want to graduate, because if you don’t return stuff they hold up your diploma.

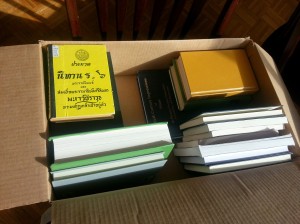

At first, I thought I was going to put them in my backpack and bike down to campus to return them. But when I stacked them up:

Scratch that idea. Oh well. I put them in a box, drove to the library after aikido class, parked illegally, and hustled them over to the book drop.

Then I silently bid them farewell.

Returning my library books means a lot of things. It means that I will be able to receive my diploma. Hopefully. If I got them all. It also means my academic career is basically over. Notice that I am not adding “for the time being,” as I have in conversation to myriad people. I have finished my MA and I am probably done.

I have mixed feelings about this.

It will be unsurprising to those who know me to hear me say that when I was in high school I wanted to get a PhD. There were probably a lot of reasons for this–I’m very ambitious but not especially interested in high power career paths; I knew that PhDs were associated with smart people and I’m smart; I went to a high school where that kind of academic achievement was relatively rare among alumni, so it would have proved how different I was (let’s face it–how superior) to my fellow students.[1]

Time wore on of course. I did an undergraduate degree and felt still interested in doing grad school, but first I went to Viet Nam for a year, came back, got a job, met a guy and fell in love, then left my job and moved in with him. At some point in there I did actually start grad school, but it wasn’t a PhD program–rather, it was an MLS[2], a professional degree designed to help me reinvent myself in a bad economy. Through a somewhat circuitous series of events, I wound up enrolled in another department, doing a second MA in Southeast Asian studies.

During this time period, I began to understand more clearly what was involved in a PhD. Unlike a BA, which you can basically get these days if you are capable of basic literacy-type tasks, a PhD requires an immense amount of reading and preparation, qualifying exams, and then basically writing a book. And the book has to be original work. It can’t be a collection of book reports or whatever. This isn’t a task where you can get someone to tell you if you have found the right answer. You are creating new knowledge; that is what people with PhDs do. In short, it’s a very stressful process.

In fact, I did some original research over the course of my MA, and that was hard.

The stress isn’t the only consideration, though when you are married it is certainly something you get to thinking about. I don’t even really need to prove how terrible the job market is for people with PhDs in the humanities–if you are curious, just go and look at any article the Chronicle of Higher Education has published in the last five years. In fact, if you have a desire to do things like: stay married, have kids, have spare time, be a novelist rather than a literary critic, have a stable income with health insurance, not be on food stamps, not have to move every few years, then you might find life as a professor quite trying.[3]

Ultimately, a combination of the above and other factors influenced me to decide that I wasn’t going to apply for a PhD. So there goes that.

It’s a weird moment. On the one hand, I know that missing out on four years of earnings and 401k contributions is not great financially, even though I didn’t take on any debt to pay for my schooling.[4] I know also that there would be no job waiting for me when I finished, and that it conflicts with some of my other life goals. And, one might argue (when talking to someone like me), given the way writers use any stupid excuse to avoid writing, consider that graduate school is really one big excuse for why I don’t have time to sit down and write another chapter of my novel.

In other words, if I want to write a novel, I should stop fucking around and do it. Now is the time.

On the flip side, though, giving up on a dream is never easy, is it? And let’s face it, PhD-holders are actually creating new knowledge through their research, which is really exciting. Getting to think about the topics they work on (in my case, philosophy and post-colonial literature and that sort of thing) is a lot of fun. Who wants to sit in an office and do technical writing when they can be thinking about philosophy?

Eventually, you have to weigh your options and make a decision about the kind of life you want to lead. What’s important to you? Stability, financial security, an exciting career, a family, having time for outside pursuits, ambition, a less stressful life, a happy marriage? Regardless of what you wrote in your “What I Want to Be When I Grow Up” paper at age 17, there isn’t a wrong answer here. Priorities can change. In fact, they should change–anyone who has the same priorities at 31 that she had at 17 is probably stupid.

I still miss my books though. I miss the excitement of learning a new language. I miss the thrill of putting little pieces of theory together and coming up with something neat. I don’t miss: the stress, the stress eating, the stress picking-fights-with-my-loved-ones, the stress crying-because-a-professor-was-mean, the sense of life-or-death about what I was doing,[5] the way academia provoked my workaholism to new extremes, the not having time for what few friends I managed to hang onto, not having time for entertainment outside of classes…

I won’t go on because I think I have made my point. I’m certainly not spending my time crying into my oatmeal about this, but neither am I resolved enough about it to bring this blog post to a happy conclusion of some kind. I am enjoying my extra time to do things like aikido, writing, home improvement projects, and triathlon training. I am also reading a lot of philosophy[6] and other books on my own, things I would never have had time for if I weren’t graduating, and I’m starting to think about teaching myself a new language. But I still miss being in classes, working in the library, researching new topics, even (to some extent) writing papers.

Being in academia sucks. Not being in academia also sucks.

The end.

[1] If you have been to high school and not harbored this feeling, well, I commend you but I think you’re lying to yourself.

[2] Technically my alma mater awards an MA (in library and information studies) rather than an MLS (which itself stands for Masters in Library Science and please don’t ask me why this is different). I only refer to the MLS here to make it clear I did two different masters degrees.

[3] Obviously the job prospects are contingent on the field. I know some PhDs who found tenure-track professorships after graduating and some who didn’t.

[4] In fact, I think I paid almost nothing in tuition for the last four years, but I worked my ass off at 2-3 jobs at a time to do so.

[5] I suppose this is true for several fields, but it seems especially bad in academia because students don’t get sick days. If you are sick, you still go to class because…you have to go to class. As an undergrad, I missed class the time I had the puking flu so bad I couldn’t stand up and walk farther than from my room to the bathroom. (As a grad I didn’t get sick.) But no one should be forced into an atmosphere where that kind of behavior is the norm. If you’re sick, you should be able to stay home.

[6] Because let’s not pretend that leaving school should ever be the end of learning. Especially at the MA level, I have the skills to continue doing advanced research on my own, although I can probably not ever publish because no one really cares what I have to say.