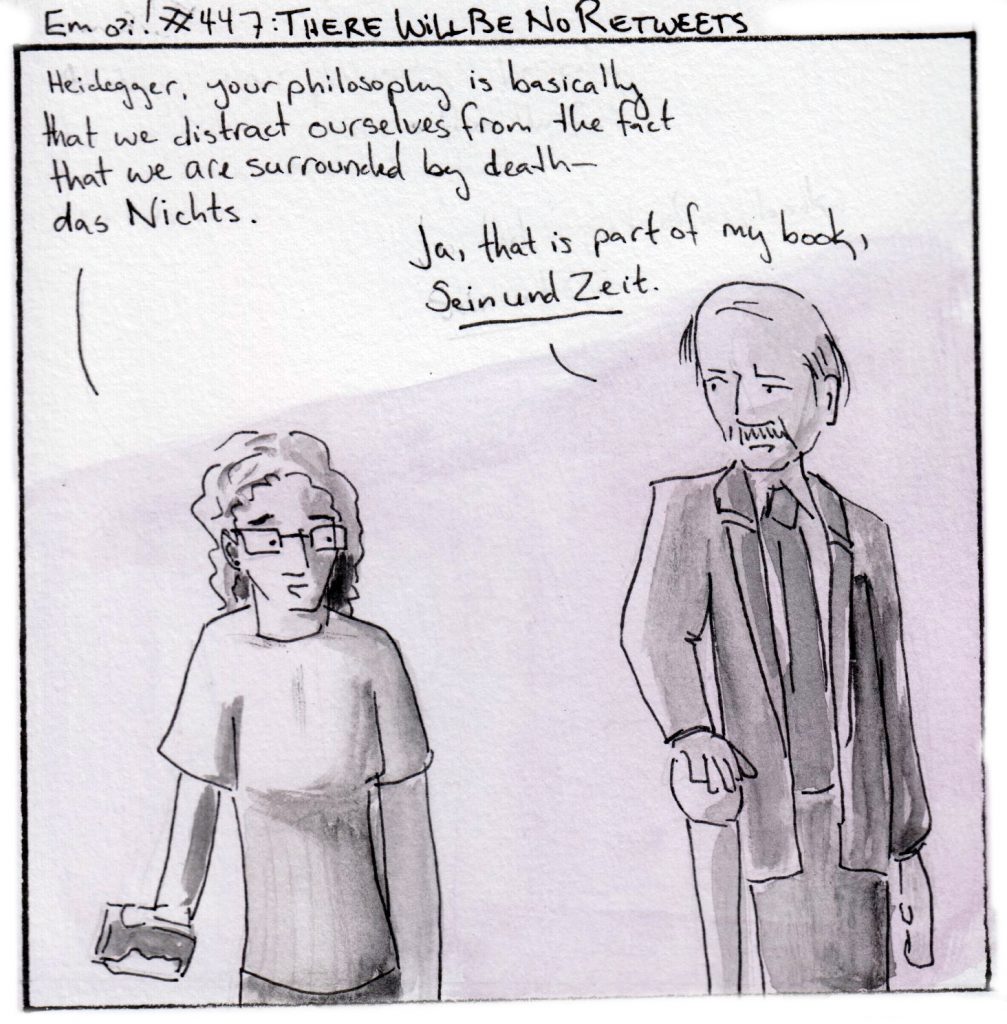

I wrote the script for this comic on May 21st, which is to say I wrote it down on May 21st–it had definitely been kicking around in my head for much longer. The “everything is reminding me I’m going to die” line was originally about COVID-19. It…still feels really relevant, but for different reasons, and as usual I feel weird for using Heidegger… so let’s talk about Heidegger. It feels like a good time to talk about white supremacy in philosophy![1]

Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) was a Nazi. I’ll lead with that, because even though his big masterwork Being and Time was written well before any of the stuff I’m about to talk about happened, his Nazism tends to feel like such a central fact to his life that I think I need to put it in front. I’m going to say in a minute that he was a more complicated guy than that appellation usually permits, but let’s not lose sight of it. Philosophically, he’s sort of loosely associated with both phenomenology (the study of consciousness from a first-person perspective[2]) and existentialism; he was a student of Husserl. His academic career benefited from his association with the Nazi party, as he was elected rector of Freiberg University, and either implemented or allowed to be implemented some of the party’s political policies, depending on who you ask and how generous they’re feeling–he may have stood up for some Jewish colleagues and helped them keep their jobs, though others claimed he denounced colleagues and blocked them from jobs, and he certainly denied student aid to non-Aryan students. During his time as rector, he made several speeches tying his philosophy put forward in Being and Time (aka Sein und Zeit) to Nazi ideology. He stepped down from his rectorship in 1934 and thereafter distanced himself somewhat from Nazi politics, although he didn’t leave the party. After the end of WWII, he was banned from teaching until 1949 as part of a denazification campaign. He became a professor emeritus in 1950 and I suppose did whatever it is that retired professors do until 1976, when he died.

This comic touches on a small piece of his philosophy, but there is a lot more. In an excellent essay in the New Yorker, Joshua Rothman writes,

Heidegger had developed his own way of describing the nature of human existence. It wasn’t religious, and it wasn’t scientific; it got its arms around everything, from rocks to the soul. Instead of subjects and objects, Heidegger wanted to talk about “beings.” The world, he argued, is full of beings—numbers, oceans, mountains, animals—but human beings are the only ones who care about what it means to be themselves. (A human being, he writes, is the “entity which in its Being has this very Being as an issue.”) This gives us depth. Mountains might outlast us, but they can’t out-be us. For Heidegger, human being was an activity, with its own unique qualities, for which he had invented names: thrownness, fallenness, projection. These words, for him, captured the way that we try, amidst the flow of time, to “take a stand” on what it means to exist. (Thus the title: “Being and Time.”)

I don’t believe he’s widely taught in undergraduate philosophy departments; certainly when I was a student at UW-Madison, he was not being taught, as far as I am aware[3]; I see now he is included in a class on Existentialism that also includes Kierkegaard, Sartre, Camus, and de Beauvoir, which is…an interesting combination there. I think his lack of inclusion is due at least as much to the fact that he’s extremely difficult to parse as his politics (although I should point out that every philosophy department routinely teaches Kant, you can’t NOT teach Kant, and he’s also difficult). On the other hand, he seems pretty popular in the amateur philosopher world–Philosophize This! did three episodes on him, A Partially Examined Life did three episodes. If you look on YouTube, there are plenty of videos like this one, which informed this comic (I count at least five other introductory videos). My rival, Existential Comics, has done a LOT of really funny comics about him.[4]

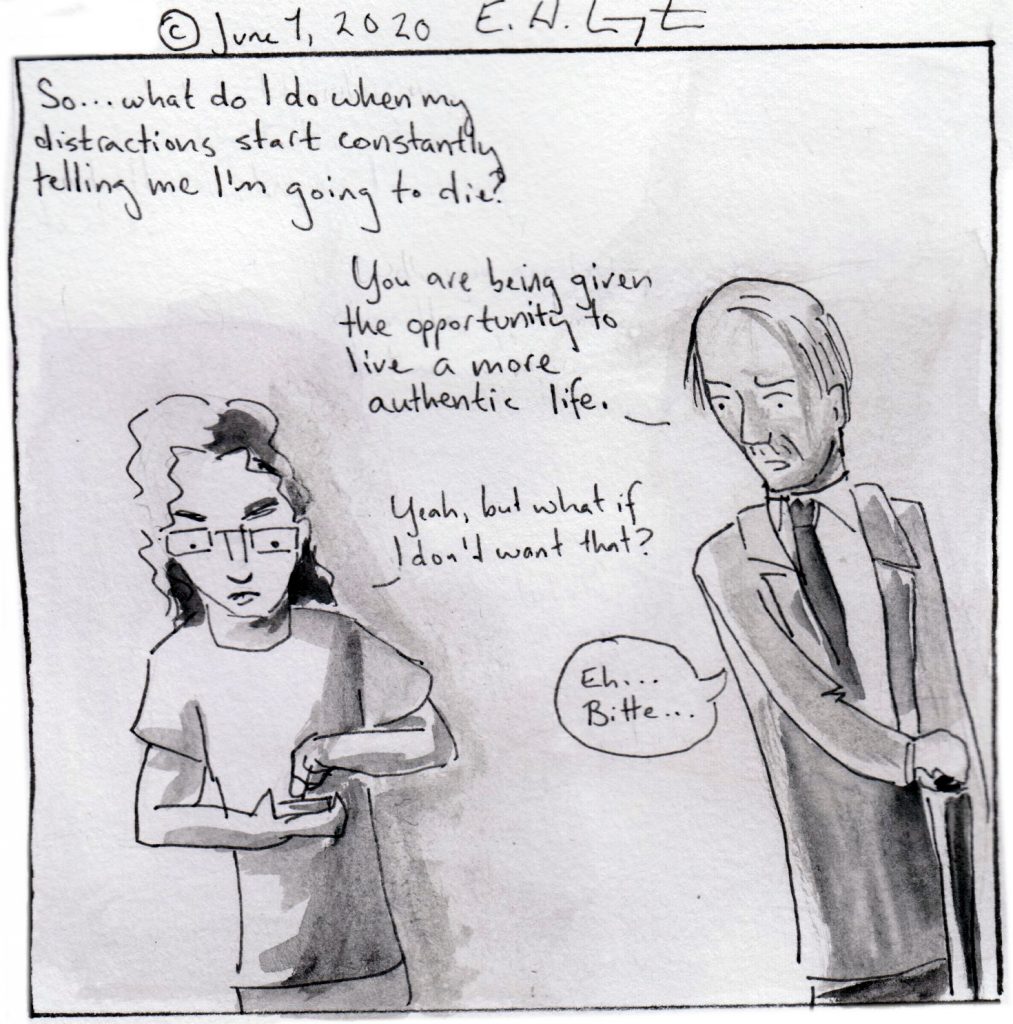

So why do we amateurs, who are not bound by the rules of academia[5] keep returning to Heidegger? Probably because his ideas have a certain resonance with us as people living in the exhausting modern world. It’s easy to see that we genuinely do immerse ourselves in distractions that keep us from thinking about the reality we’re dealing with; our experiences are rarely unmediated, whether it is because we are continually viewing things through our phone’s cameras or reacting to things online rather than engaging with them in real life. Being and Time was written in 1927, but it still feels very contemporary and relevant. As an environmentalist, I wholly support the idea that people need to get more in touch with nature in order to get more in touch with their authentic selves (at one point, Heidegger recommends taking long walks in the country). As a specifically difficult text, it also probably engenders a certain amount of satisfaction in the readers that leads them to want to talk about it, which may also account for some of the fascination. Or, quoting Rothman again, “You don’t spend years working your way through “Being and Time” because you’re idly interested. You do it because you think that, by reading it, you might learn something precious and indispensable.”

Heidegger also has the advantage of having been defended, pretty ardently, by Hannah Arendt (this is the complicating part of his biography), who was herself a pretty legit philosopher and also a German Jew. She was also a student of Husserl’s who briefly studied under (and had an affair with the married) Heidegger before completing her PhD in 1929 (Germany was a pretty cosmopolitan place at the time); she then fled Germany in 1933. She defended him post-war, even knowing that he had been a Nazi. This is sort of where his biography gets tricky, because both their relationship and the extent of his Antisemitism weren’t really known about until after his death. He also wrote some stuff in his last book, Only a God Can Save Us, that suggested he was at least disillusioned with Nazism by the end. Of course, with him being dead for like 40+ years at this point, we can’t exactly ask him to weigh all of this and explain, and even if we could, what credence could we attach to his explanations?

Is Heidegger really such an important part of the history of philosophy that we need to keep talking about him? This question comes up a lot when dealing with former Nazis, and in a lot of cases the answer has been, “No, we should chuck the Nazis out”–but coincidentally, this seems to be the choice when the results of whatever research they were doing is rubbish. For example, the medical community doesn’t pay any attention to what Mengele did[6]. On the other hand, Wernher von Braun actually…designed the Saturn V rocket. So, you know. In a broader sense, this is a question that comes up again and again with reference to what has been termed “cancel” culture, whereby a mob will publicly shame someone, typically a celebrity, for real or imagined crimes, and then basically try to ignore that person, cutting them out of society. Does the person get to resume their livelihood? When, if ever? No one is quite sure yet.

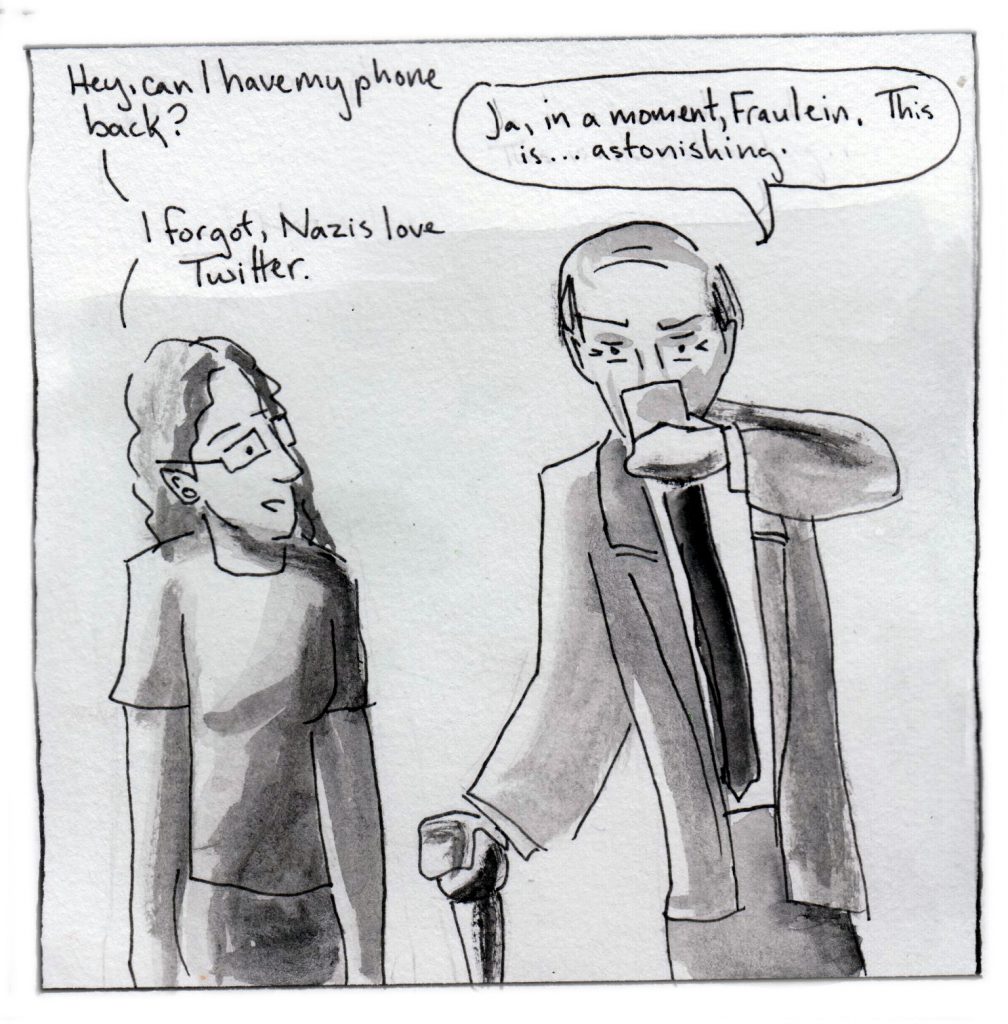

For me, the question could be framed more specifically as “Why do I continue to return to Heidegger?” There are ultimately a few reasons. First, there is something compelling about this tiny piece of his philosophy that speaks to me, just like it speaks to so many others. Second, I take a perverse delight in co-opting the philosophy of someone who would have been unhappy about the idea–Heidegger blamed a lot of the modernization he hated on Jews, and saw them as “uprooted from Being-in-the-world”–i.e., incapable of authenticity (Rothman’s quote and summary), so for a Jew to demonstrate the same anxieties and concerns with modernity that he does has a certain ironic appropriateness. Drawing him providing advice to me, someone he probably would not have had time for in life, is extremely funny to me. Third, I like to use him to remember that even smart people can be seduced and make extremely terrible decisions, and that it is a good idea to stop and think things through once in a while.[7] Reading more about him, Heidegger is basically the banal kind of evil you meet every day, a bureaucrat looking for an edge more than a guy personally shooting babies, just rules-bound enough to make life a little more difficult for everyone. But at the same time, I have to feel like maybe there aren’t any innocent Nazis, just like there aren’t any good cops.

But. More and more, watching the George Floyd protests, I’m reminded that a lot of normal people in Germany were probably like Heidegger–secure in their privilege, and not very brave. No one, on a day-to-day basis, stands up to the police, because there’s no accountability, so people have literally taken recordings of people getting murdered in front of them and yet done nothing to intervene with the actual murder. I don’t know if we can exactly blame anyone for not wanting to put their own lives on the line; in part, perhaps it’s a demonstration of how afraid people are. The cops aren’t going to come over here and start busting heads, so we can film them, but if we try to intervene, well–who knows what amount of restraint they’re willing to exercise. (Having written this and then watched a week of protests, I can tell you the answer is “none”–it doesn’t matter who you are, the police will beat you if you get in their way.) You might have called these people collaborators in Nazi German, but looking at the way people in the US have been about, for example, the Trump Concentration Camps at the border, ICE abuses, the long-time abuse of civilians and especially Black people by the police, etc., etc., I think that might be a little strong. Collaboration implies active participation or approval in some way. Heidegger was, arguably, in the weakest sense, a collaborator. Instead, I think we could say that these problems are so big, pervasive, difficult, and frightening that instead of facing them (for longer than a few news cycles), people tend to retreat into das Gerede–the chatter that distracts us all from the Real. Now that the typical outlets of das Gerede (Twitter, Instagram, FB, Reddit, Imgur, etc.) are all full of images of protest and conflict, we have nothing to distract us. The problems will be faced; they must be faced.

Whenever big protest movements come up, people seem to think in terms of the things they would lose were the movement’s ideals to be enacted, both explicitly and not. Defund the police? Then who will find our stolen cars? Give women rights over their bodies? Then how will we be able to keep them powerless at home? If I told you to stop teaching Shakespeare, you might rightly protest that there would be a huge gap in the curriculum, leaving out some of the greatest works of literature in English. But because any class has a limited number of hours per week, limited weeks per semester, and students have a limited number of semesters in the time they spend at school, leaving things out can also offer the opportunity to add things in that are now overlooked. Already any philosophy curriculum suffers from history–there are so many philosophers from Thales onward. Who could we include if we didn’t spend time on Heidegger? What level of excellence would it have to attain to be worth the trade off?

There’s a kind of false argument people often bring up when affirmative action comes up that suggests that if you decide you’re going to try to hire someone nonwhite, someone nonmale, you’re somehow giving them the job out of pity, because they couldn’t possibly just be the best candidate for the job. But I think one thing we’ve learned is that they often are the best candidate, and without diversity initiatives we would have overlooked them and hired another mediocre white guy. So I want to start a diversity initiative in philosophy, and make the claim that just because there are a lot of smart white guys, maybe there are some philosophers who also have interesting, illuminating, even genius things to say who are different from the milieu. This is my modest proposal–no matter how much we are willing to smooth over Heidegger’s crimes, no matter how much of a singular genius he may be (and I think more and more that this is a myth, there is no such thing as a singular genius), maybe we could do better.

It has been difficult for me, sitting at home, to not be able to protest. I feel like words are no longer useful (who needs another think piece? The answer is always “no one”), but words are all that I have to give (I mean, you can give money too–see this next footnote for some resources[7]). Words about the way philosophy is studied are the smallest potatoes imaginable; it’s just an area I feel like I have a little bit of something to say about that maybe other people aren’t already talking about in a better way. So I press on against the current, borne ceaselessly back into the past.

Join me next time, we’ll do Fanon.

Citations:

In addition to Joshua Rothman’s article linked above, this essay benefited from:

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Heidegger

Martin Heidegger on Wikipedia

Heidegger and Nazism on Wikipedia

Hannah Arendt on Wikipedia

Hannah Arendt on Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

The title is from Amanda Palmer’s album There Will Be No Intermission, aka the album most likely to make me break down in sobs in front of my computer. Saddest song. Favorite song.

[1] After I started working on this, I realized I had a lot to say about the “canon” of philosophers as taught in normal classes (or even as philosophy afficiendos, the philosophers we most pay attention to), who are pretty much exclusively white and male until you get into the late 90s and after, and then still like 90% white and male, as well as the deficiencies of my undergraduate education in general. But this essay is already over 2,000 words long, so I have not said every thought on the matter.

[2] Other major phenomenologists include Hegel and Kant.

[3] I took mostly classes on Philosophy of Science, so studied philosophers like Frege, Russell, Wittgenstein, and Godel, as well as a fair amount of Plato. So it’s possible they were doing classes on Heidegger and I just wasn’t interested at the time. Side note–other major philosophers mentioned here who are not being taught: Husserl and Arendt, both of whom were Jewish. And I do not recall reading any texts by major philosophers of color during my tenure there (we barely read any women–only in my ethics course, really). Side side note, it’s interesting how almost every concept in philosophy is attached to the person who thought it up with the exception of the trolley problem, which is very widely known but most don’t know it as the brainchild of Philippa Foot. Interesting.

[4] Just kidding, we’re not rivals. They’re great.

[5] Rule one: thou shalt stir up benign controversy so people will cite your paper

[6] This is what I have been told, anyway. I have not been able to discover any articles with a cursory search.

[7] It’s worth noting that Heidegger’s disenchantment did not come from, like, the mass murder parts of the Nazi philosophy, so even smart people can make relatively huge errors in judgement.

[8] Free the 350 Bail Fund is the bail fund for Madison, WI. And this site lets you split a donation among several different worthy organizations. And there’s always the ACLU.