I cut this up into panels for easier viewing. Click here to view the original.

A few notes and sources:

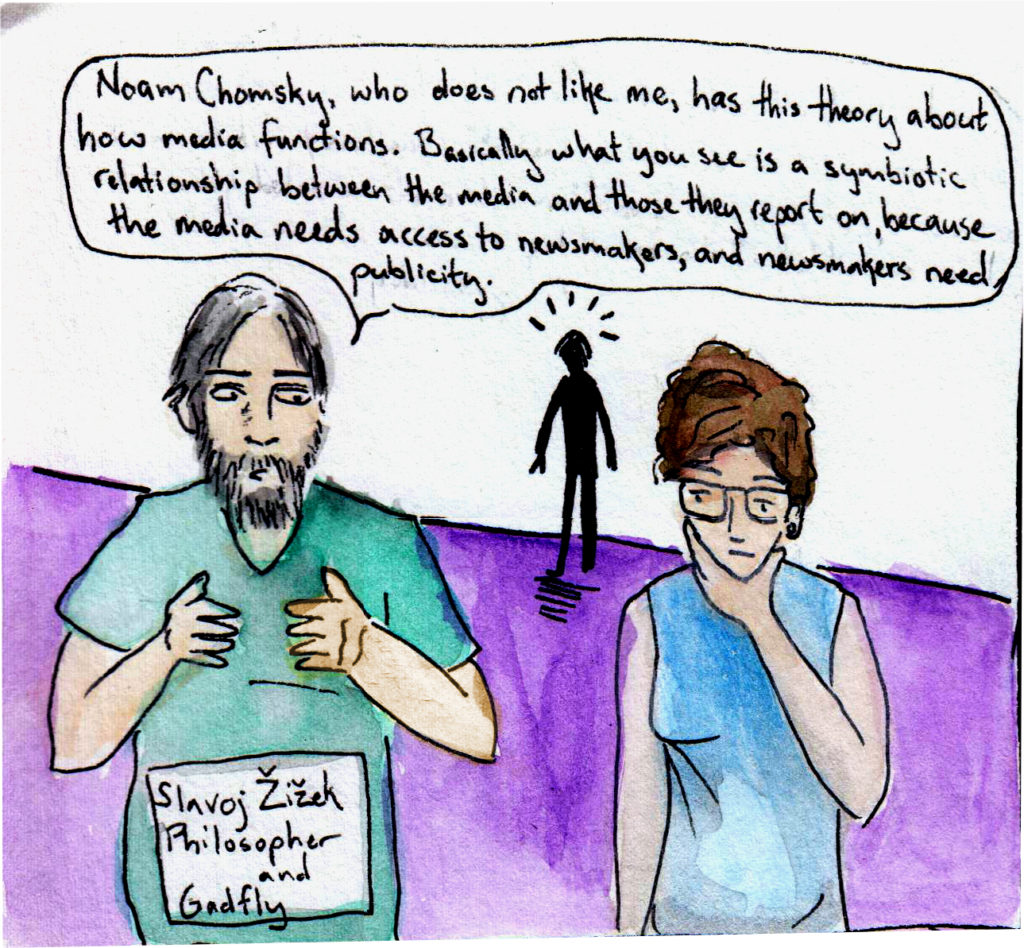

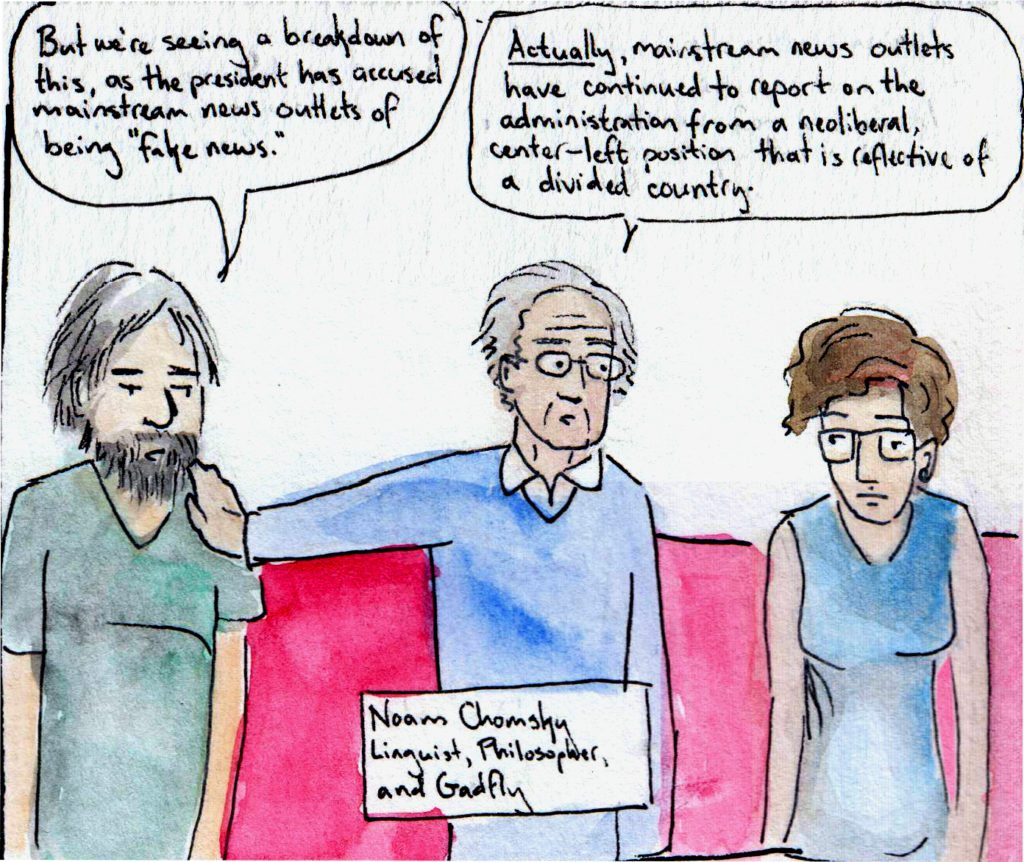

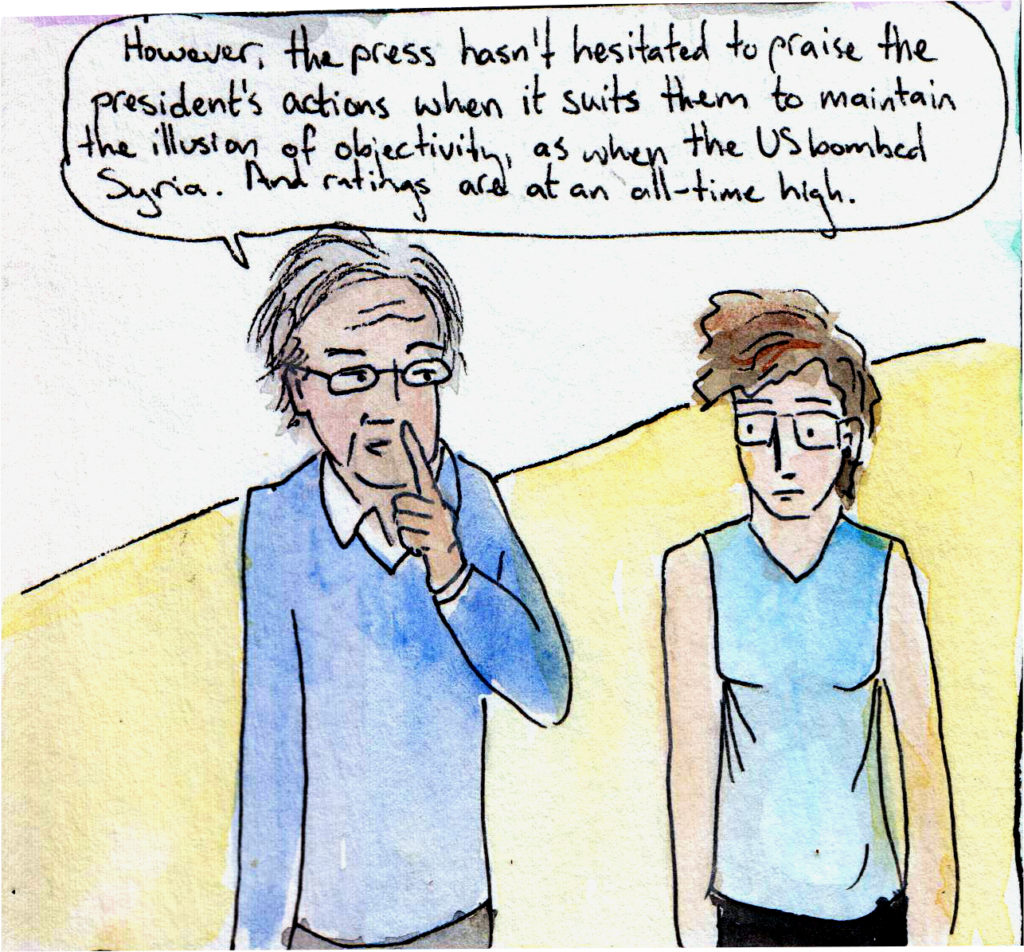

- Chomsky didn’t develop this theory (properly called the “propaganda model”) alone–he co-wrote the book with Edward Herman. Wikipedia suggests that the theory was more Herman’s than Chomsky’s, but everyone seems to call it Chomsky’s theory. Here is a video that explains it in more depth than one panel of a comic can do. As a (former, I guess) southeast Asianist, I have mixed feelings about Chomsky…he seems to be generally accepted on this point, but he was so, so wrong about a number of things (specifically, the Khmer Rouge)…

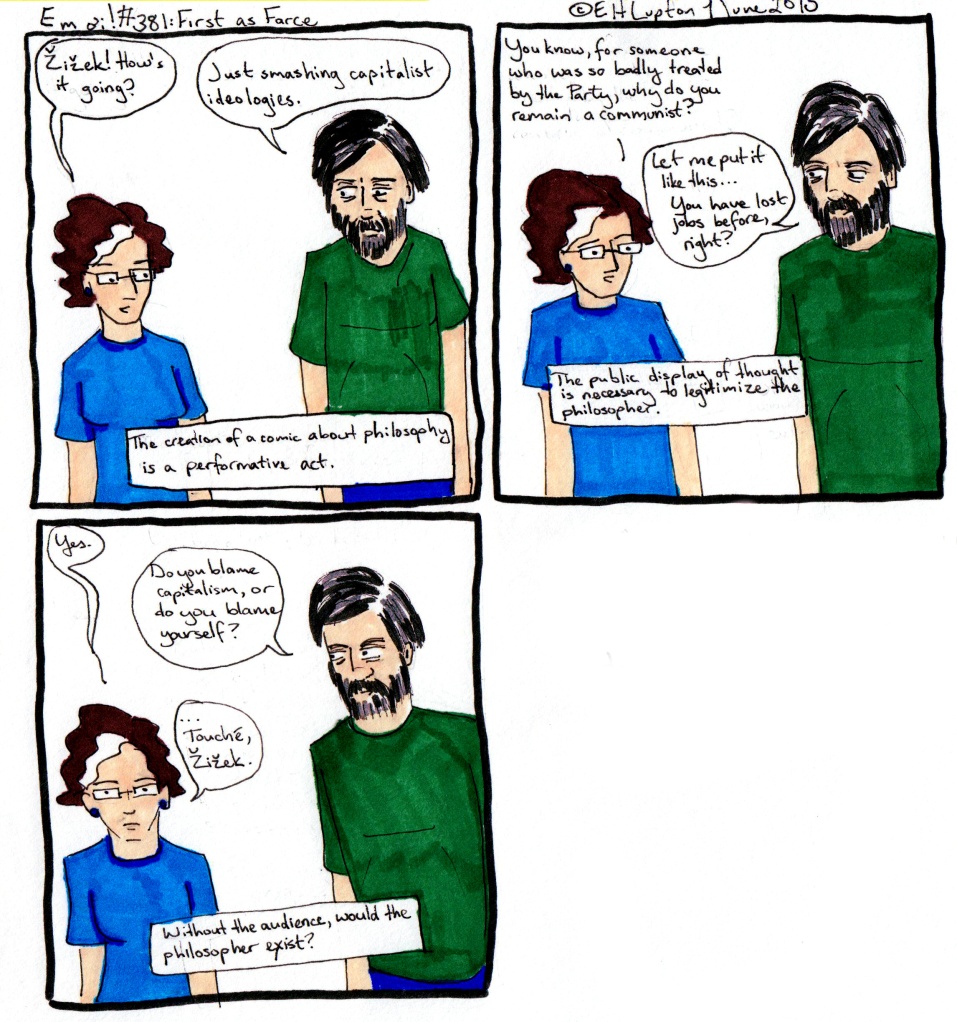

- Here is the main interview with Zizek that I referenced. I do enjoy the contrast between the well-dressed BBC host and the Ziz, who always looks like he has been awake for about 43 hours and hasn’t done laundry in a week.

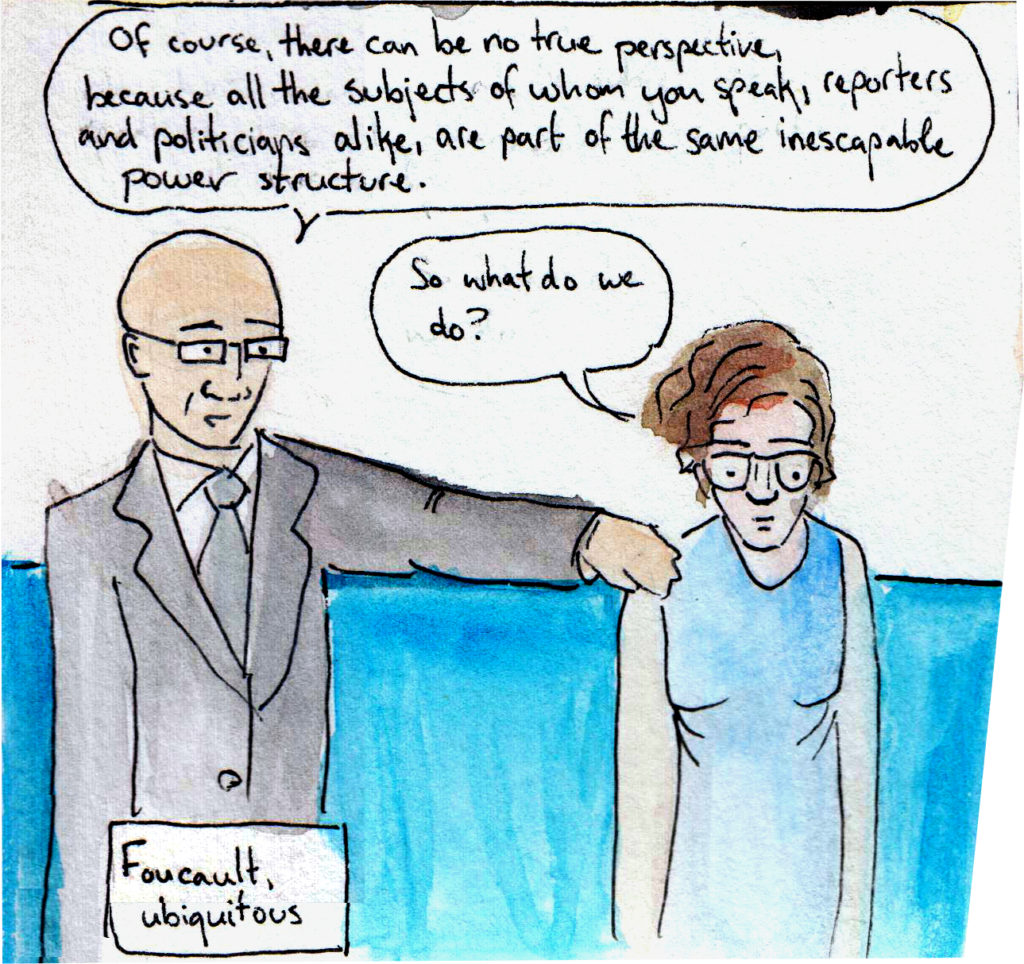

- Foucault’s stuff about the power structure and revolution was touched on in this earlier comic.

- Fitzgerald has a weird face. Sorry, dude. Of all the real people I’ve tried to draw, he is the weirdest. And this is including J-P “Walleye” Sartre.

- Chomsky and Foucault didn’t get along either.

Chomsky was, (possibly) surprisingly, on the side of Hillary Clinton during the last election, while Zizek wanted people to vote for Trump–not because he supported Trump; in fact, he views DT as immoral and terrible, in many ways a total disaster. But he believed that by electing DT, the left would see some galvanization and would begin to reconstruct itself, not just to offer opposition but to offer a viable alternative that did not include neoliberalism/late-stage international capitalism/what have you. Interestingly, I think he was right to some extent. I knew a few people involved in local activism while Obama was in office, but I now know many, many more people who are calling their senators and congresspeople regularly, going to rallies, and actively supporting various campaigns to change the country for the better.

As I’m writing this, however, DT has pulled the US out of the Paris Climate Accord.* What this will actually mean for the world in the long run is difficult to say at this juncture, since it was a largely symbolic voluntary agreement that many (well, Honduras Nicaragua [ed: damn it]) claimed didn’t go far enough. But I do think that without the governmental impetus, the solution to global warming will wind up coming from the business community–that capitalism will eventually have to save us. If the idiotic old men in power can’t see the writing on the wall, the entrepreneurs can, and in this country money speaks a lot louder than treaty obligations. Which is ironic, because I think that the revolution Zizek had in mind was not essentially the renaissance of cultural capitalism in the role of savior, but (of course) socialism (“the good old welfare state,” as he would put it). To paraphrase Oscar Wilde (or, really Ziz quoting Wilde in the video linked just there), it feels like a bad idea to use private industry to lead the mitigation of the environmental disaster caused by private industry, because their motives will always be profit-driven rather than altruistic, and that means that people not living in the first world are going to wind up getting screwed somehow. On the other hand, as someone who is worried about the environment, I guess I’ll take what I can get at this point?

Circling back to the Ziz’s point about the president as the motive for revolution: the problem is that Trump is a good enemy but ultimately inept. The left doesn’t really have to do anything–they (we) just have to stand there and he’ll turn his administration into a dumpster fire. It’s been less than six months and there’s already been talk of impeachment on the floor of the House by Republicans. Thus, while the base is fired up, the democrats in congress don’t seem to be doing much in the way of providing alternative leadership or pivoting to embrace the more liberal Sanders wing or the multicultural Obama wing–they don’t have to.

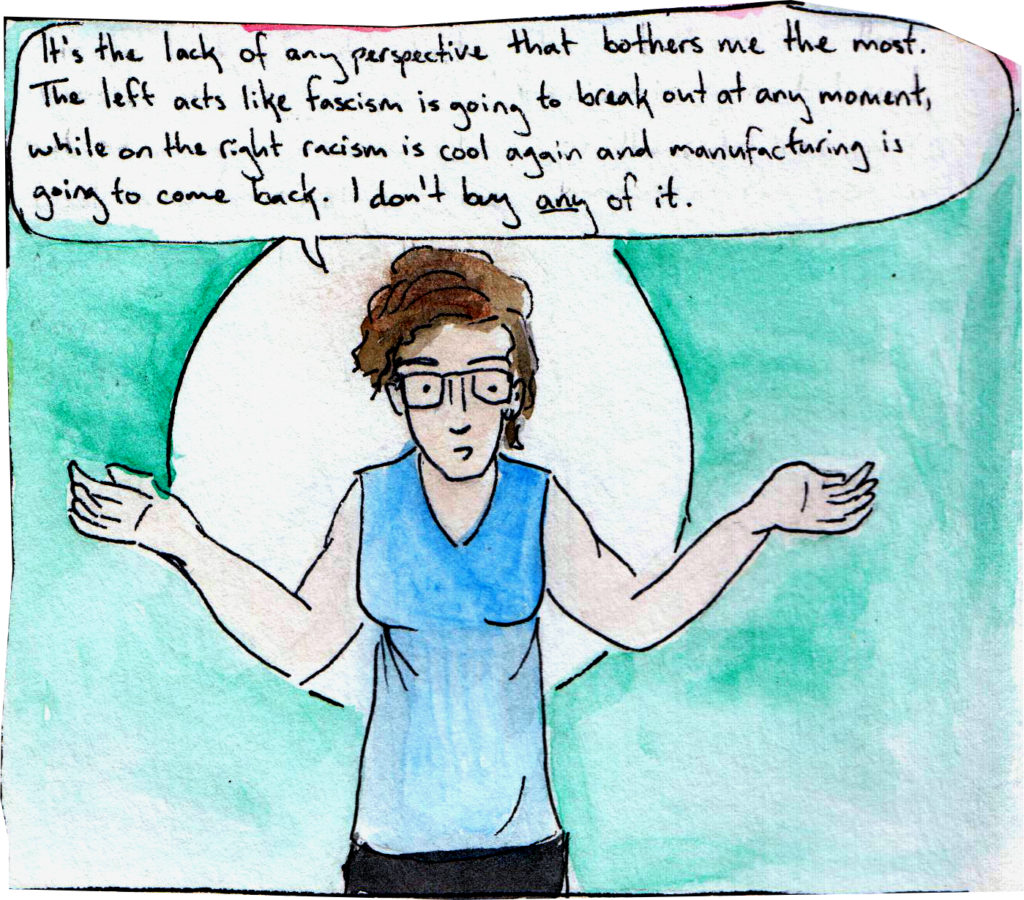

And this is where the lack of objectivity I mentioned begins to bother me–rather than seeing any individual action the administration takes as the flailing of an inept and failing regime, the leftermost voices seem to spend an inordinate amount of time on interpreting how this is going to lead to fascism/autocracy/A Handmaid’s Tale/insert your particular fear here. I suppose this is the reverse of Obama, or perhaps more accurately the flip side of it. I discussed a few posts back seeing voters in 2008–especially African American voters, since I was in a heavily African American area of Philly–reconstructing Obama in their own image so that he could serve as a vehicle onto which they could project their ideas/hopes/dreams. Now on the other side, we have the left projecting its fears onto DT–perhaps because of a lack of transparency on his part that keeps him feeling like a remote and unknowable figure, or perhaps because this is how people always deal with their leaders–just as we must imagine that we live in a community filled with others who are basically the same as we are in order to become a nation, we must imagine the same thing about the leader who we will likely never meet in person–that he or she is a specific type of person that either is like us (for those leaders we like) or totally foreign to us (for those we hate).

To provide a possible counter-point to my own point here, I’ll add that while I was sketching out this comic, I found this video on Jacques Lacan,** about whom I know very little (he is widely admired by many of the continental philosophers I mention here, especially Zizek, but not widely discussed in the [undergraduate] philosophy curriculum, possibly because he’s largely still seen as a psychologist? Or because undergrad philosophy is kinda naff in a lot of ways). Anyway, the video quotes Lacan as saying, “What you aspire to as revolutionaries is a new master. And you will get one.” Lacan meant that what people want, from the time of infancy, is basically an “ideal parent,” someone who can make everything okay, and we carry this desire into who we vote for. Whereas it is better, following Sartre’s idea of radical freedom, to accept that no leader is going to be able to do these things, and instead to embrace the fact that if we want something to happen, the best way is to make it happen ourselves. Go out and break glass ceilings, clean up the environment, make art–do what you need to in order to be awesome every day.

We’ll file this under P95.82 U6 L86 2017, for Philology. Linguistics–Communication. Mass media–Special aspects–Political aspects. Policy–By region or country, A-Z. This allows it to sit next to the original being referenced, Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of Mass Media, at least at my alma mater.

Footnotes:

* When I say “pulled out,” it’s not clear how Bloomberg / the individual states and cities saying they’re still going ahead with the Paris Accord requirements plays into this argument. Bloomberg is of course a total centerist neoliberal (and so on and so on).

** Yes, I watch stuff like that for fun.